Briefly, How Sound is Generated

Sound can be captured in a wave, and we hear sound because the air transmits sound waves which are picked up by our ears. If we can create waves (the audio data), we can feed that into a speaker which will vibrate the air, replicating the sound.

We have a 6 bit DAC made with a resistor network. There are 6 GPIO pins which will either be on or off. The resistor network is ‘binary weighted,’ so every resistor will be double the previous one going in one direction, and will be half the previous one going in the other direction. Now you can convert binary, digital, data into analog data, because you can now represent voltages in between 0V - 3.3V in increments of 3.3 / 6 (the more bits you have, the more precise values you can get).

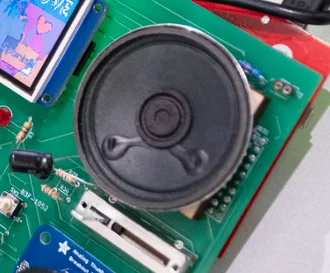

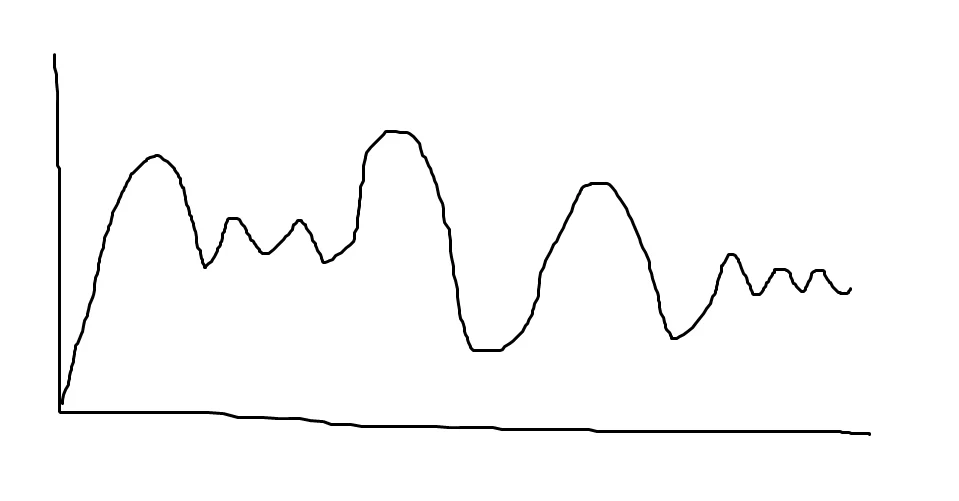

Say you had audio data which looks like this:

The x-axis is time and the y-axis could be anything, but its a magntiude kind of value (you can think of it as a voltage, and for these purposes it probably will be). With the DAC, we can add up the voltages to get a pretty close value of the waveform at any point on the wave. By constantly changing the DAC value, we can get basically any sound we want.

Two DACs

Since we weren’t going to deal with digital signal processing (DSP), we just have two DACs. One DAC plays sound effects, and the other plays music. The sound effects are easy, there will just be an array of “dac out” values which will form the audio signal of the sound effect. The music is a whole different problem.

Music

We weren’t settling for some short, low quality background track which just plays the whole time (turns out we wouldn’t have enough ROM for it either). We wanted to play our favorite hits, including “Never Gonna Give You Up.” To understand how ridiculously large songs are, Rick Astley’s most well known hit, when reduced to 6 bit quality, takes up 2,544,614 bytes. Two MILLION bytes, that’s 2 megabytes (really 2.5 or 2.6). There is now way that can fit in our pathetic kilobyte based microcontroller. But you know what can make megabytes look tiny? That’s right, a gigabyte. Where do we get a gigabyte from? An SD card.

SD Card Interfacing

I’m going to skip over most of the details when interfacing with the SD card, it’s copied magic code. The important thing is to play the song smoothly, there needs to be a double buffer, similar to graphics. Reading and sending data from the microcontroller will basically always be slow compared to its processing speed. If we load data from the SD card, play it, load it again, play it again, there will be noticable breaks in the song, although you may find out the microcontroller is faster than you think because these breaks are tiny. This is not “good enough,” we need to remove the breaks. The way this is done is basically mulithreading. While we are playing one chunk of the song, we are loading in the next part. You need to be careful with setting global flags and checking things properly, but it is not too bad if you really think about it.

Here is the important code for streaming audio.

Two Microcontrollers

Streaming audio takes a lot of processing time. My laptop I’m using to write this post can do it effortlessly amongst many other tasks. The tiny, weak, TM4C123 doesn’t stand a chance. There’s a simple solution though, two microcontrollers! One will handle the game’s logic and drawing, and the other will be dedicated to sound. If you’re fancy with old video game consoles, you may know they had dedicated sound chips (I really have no clue if modern ones or even laptops/desktops still have dedicated sound chips, a quick Google search will tell you for sure).

Since we have two microcontrollers we need to figure out how they will communicate with each other. They will be using the UART protocol, but we still need to add our own layer on that (UART is link layer, see the OSI model if you do not know what I am talking about). We are using the jankiest, least sophisticated system possible. Whenever the game microcontroller (GM) sends one byte to the sound microcontroller (SM), the SM will interpret that and play the corresponding sound effect or switch songs (it can even stop playing songs). There is no error checking at all, so a song may ‘randomly’ start playing when powering on due to electrical noise. The most significant bit determines if it’s a song or sound effect, and the rest (leading to 128 combinations), is what song or sound effect to play.

Code

This is the entire sound “project” which gets flashed onto one of the microcontrollers